Post-Contact (1862-1920)

(Notes related to the Rainier Valley and 98118 zip code are in bold and italics.)

“The 98118 ZIP code covers about six square miles, from Genesee and Beacon Hill in the north to Rainier Beach in the south, between Lake Washington on the east and Martin Luther King Boulevard and Interstate 5 on the west. About 45,000 people live within its boundaries, in neighborhoods that range from upscale (Lakewood, Seward Park) to grittier (Hillman City, Rainier Beach)… The Rainier Valley was formed by glaciation, and the valley is a depression between two ridges, Beacon Hill and Mount Baker Ridge, not a river course.”[1] - HistoryLink

November 10, 1862: Washington State hand-drawn plat map (cropped) of Township No. 23 N. R + E of the Willamette Merida in the Territory of Washington. The current yəhaw̓ site is located in the NorthWest quadrant (smaller square) of zone 2 (larger square) near the “Dawamish Lake” aka current-day “Lake Washington.” SEE FULL MAP.

June 30, 1863: Washington State map. SEE SIMILAR HAND-DRAWN MAP.

In 1869 was when Seattle became the first municipality in King County. Records after 1870 were found at Puget Sound Regional Archives.

September 9, 1870: First record of 117.61 acres – which included this site – being purchased by Fletcher J. Hawley, a white settler who began settling in the Seattle area as early as the 1860s.[2][3]

The Rainier Valley area was slow to develop due to its wetlands and heavy forests of “great strands of fir and hemlock,” which made farming difficult because logs had to either be floated down the river or skidded overland.[4] The only non-Native inhabitants in the area at the time were a few farmers north and south of what would eventually be Columbia City.[1]

January 14, 1876: Fletcher J. Hawley (and Marion C. Hawley) sold the land to Fletcher’s wife’s brother, Thomas Canfield (listed Thos. Canfield).[5][6]

Canfield was a well-known businessman from Burlington, Vermont who helped negotiate government contracts which led to the development of the transcontinental Northern Pacific Railway, which ran from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest and was approved by Congress in 1864. Construction for it began in 1870.[7] Canfield served as one of the company’s directors until it went bankrupt in 1873.[8]

1879: King County map. SEE FULL MAP.

1880: King County map. SEE FULL MAP.

In the 1880s, Rainier Valley was still relatively undeveloped. But this was around the time the first interurban train opened. Seattle boomed to 10 times its population in the 1880s as a result.

Guy Phinney built a large sawmill at the foot of Charles St. which “was capable of producing 75,000 board feet of lumber a day,” and two of its facilities were connected by a tramline. The mill continued to operate until 1910.[4][9]

1890: According to residential property records, two houses were built at “9658 51st. Ave. S - PARCEL #713130-0082,” though another source says 1900. The nicer 2-story house has six bedrooms and two toilets with a concrete porch; the less nice 1-story house has two bedrooms and one toilet, with a fireplace for heating.[10] These houses are not part of the collective’s current site, but were likely linked historically.

Around 1899, a banker named J.K. Edminston received permission from the City of Seattle to build a streetcar line called the Rainier Avenue Electric Railway, which picked up development in the area. It was taken over by W. J. Grambs in 1890. By 1891, it was seven miles long and reached Columbia City, sparking development in the valley and the transportation of produce, lumber, and people. “Tall trees still lined the right of way and passengers sometimes reported seeing bears in the old-growth forest.”[4]

However the company went bankrupt in 1893 due to the “Panic of 1893” depression. It was purchased in 1895 for $14,300 by a man named Frank Osgood, who “furnished the line’s original electronic equipment.”[11]

Interurban car at Wildwood station, Rainier Valley, Seattle, ca. 1905. Public domain image courtesy of Webster & Stevens.

A year later, the Seattle and Rainier Beach Railway Company emerged, and in 1896, it expanded an additional 5 miles to Renton. Thus, the total length of the system was 12 miles – making it the longest electric railway in the state and the first to make an interurban connection. “Passengers paid five cents to travel from Rainier Beach to Columbia City and five more cents from Columbia City to Seattle, the first experiment in zone fares. Trains ran every 45 minutes.”[4]

The rail company grew between 1895 to 1899 and was worth $90,000 by the end of that period. By 1900, freight and passenger needs had expanded rapidly.

July 19, 1899: Thomas Canfield and his second wife Caroline Canfield sold the land to Edward F. Sweeney (E.F.) and Moore Investment Company,[12] a company founded by James A. Moore.

Moore developed much of Capitol Hill, University Heights, and other neighborhoods in Seattle, using funding from large East Coast investors. He also developed major, iconic buildings across the city, including the Moore Theater. By 1901, he was platting large parcels – or dividing them into different plots – and putting individual lots on the market.[13] James A. Moore was also responsible for the creation of the ship canal which connected Puget Sound with Lake Washington via Lake Union; that ship canal would forever lower the water levels in Lake Washington and change the watersheds of the area.[14]

Sweeney was the founder of the successful Seattle Brewing & Malting Company and later became very involved in real estate, particularly after 1906.[15] This site must have been one of his earlier real estate ventures, and the Rainier Beach Garden Tracts document lists him as the individual who platted the land.

August 10, 1899: E. F. Sweeney sold the land to Miss Julia A. Butts, the daughter of a Civil War soldier,[16] and Arthur A. Kenworthy.[17]

August 17, 1900: E. F. Cummings notes that Arthur A. Kenworthy’s mortgage is satisfied.[18]

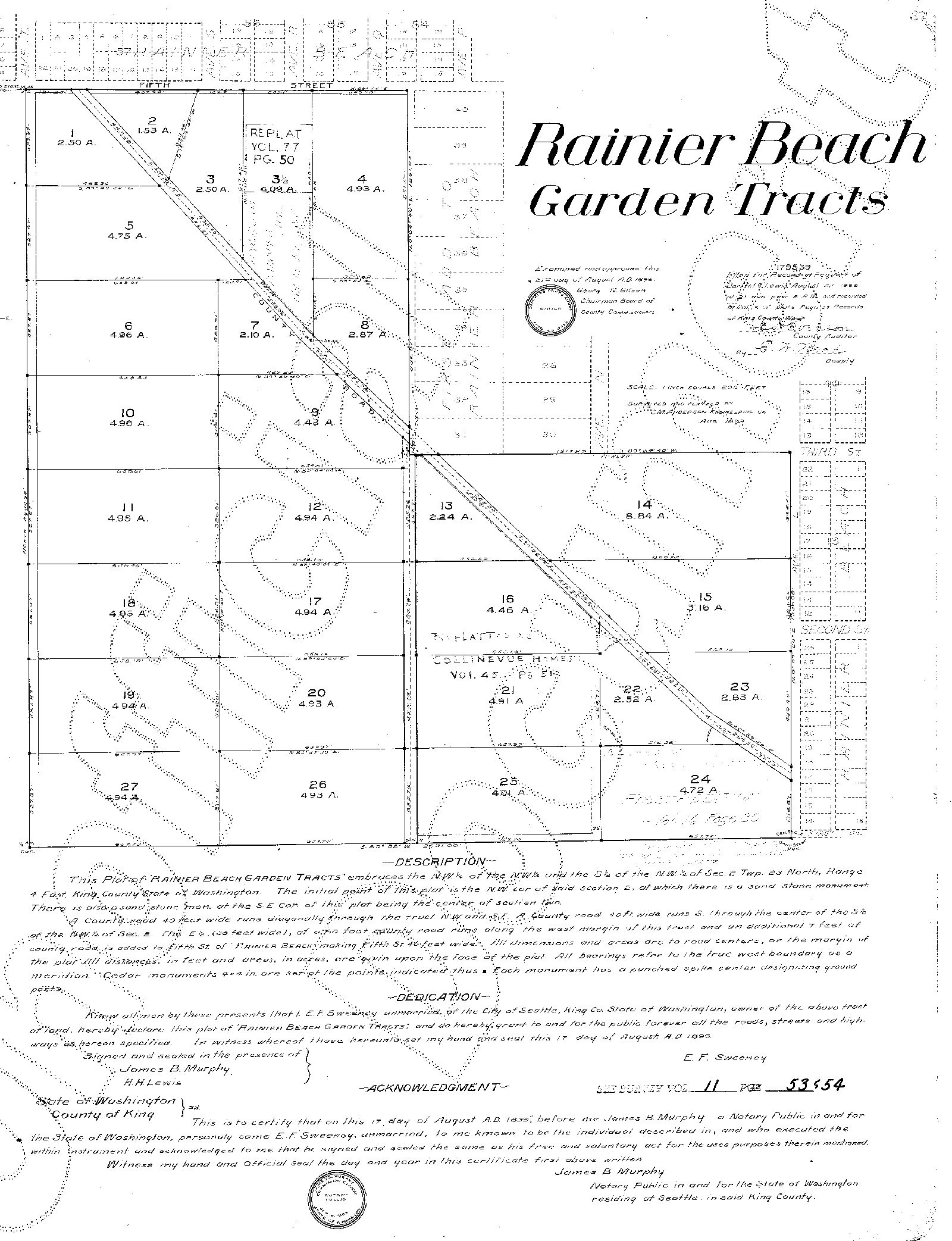

Document showing that the Rainier Beach Garden Tracts were platted in August 1899. In some early documentation, the Rainier Beach Garden Tracts were called “Sturdevant’s Rainier Beach Garden Tracts.”

In 1899, the land which includes the current yəhaw̓ parcels was platted – or divided up – into the 27 different “Rainier Beach Garden Tracts,” then sold off individually. What is listed below are those relevant to yəhaw̓'s current tracts – portions of number 5 and 6 – though the overall area is much larger. VIEW FULL MAP.

1905: C. K. Sturdevant owned about ⅓ of the Rainier Beach Garden Tracts parcels; others were owned by a number of different people.[19] This changeover of ownership in the tax rolls is a bit of an anomaly.

1920: Kroll Atlas of Seattle map of the Rainier Beach Garden Tracts; yəhaw̓’s site is split between tracts 5 & 6. SEE FULL MAP.

In the early 1900s, Italians were attracted to the area due to coal mining jobs in Renton, New Castle, and Black Diamond; they settled near Rainier Ave. S and S Atlantic St. They planted large gardens, and sold the produce at local markets, thus giving Rainier Valley the nicknames “Garlic Gulch” or “Little Italy.”[4]

Japanese immigrants also bought plots in the valley around this time, though they often had to go through a white intermediary in order to do so, as they were prohibited from purchasing land at the time. (See “Kubota Gardens” section below.) They tended to have their farms closer to Auburn and Kent.[9]

In 1907, the City of Seattle annexed Rainier Valley to Lake Washington, and south past Rainier Beach.

1910: Julia A. Butts owns a large 2.375-acre parcel, including the yəhaw̓ site; other nearby parcels are owned by other members of the Butts family; Arthur A. Kenworthy also maintains a nearby parcel.[20]

In 1910, sawmills started by Guy Phinney in the 1880s ceased to operate in the area.[4]

By 1916, most land south of Holgate Ave. S and 25th Ave. S – including where yəhaw̓ is located – still had not been developed.[9]

1915: Unclear through the tax rolls – which are maintained on a 5-year basis – though it seems Arthur A. Kenworthy may still own much of the land.

1919: Olivia R. Thornton owns all parcels relevant to yəhaw̓.

In 1920, the first lumber yard was constructed by W. G. Savage Lumber Company in Rainier Valley. Following it, housing expanded across the entire Rainier Valley throughout the 1920s. Most of Rainier Ave. S was also zoned for commercial use, thus leading to a number of businesses and industrial shops.[9]

Hill Street looking east from Rainier Avenue, Seattle, Washington, 1914. House in left foreground is still there a century later (it's painted white as of 2015). Item 6599, Engineering Department Photographic Negatives (Record Series 2613-07), Seattle Municipal Archives. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. Attribution: Seattle Municipal Archives.

Rainier Avenue at the corner of S Weller Street, Seattle, Washington, U.S., 1918. This would be looking slightly east of south. Beacon Hill is on the right. As of 2021, the Nihon-go Gakko (Japanese Cultural Center) is just up the hill half a block to the left of the camera position. Item 1535, Engineering Department Photographic Negatives (Record Series 2613-07), Municipal Archives. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. Attribution: Seattle Municipal Archives.

Tate, C. (2012b, August 13). Southeast Seattle ZIP code 98118: Neighborhood of nations. Southeast Seattle ZIP Code 98118: Neighborhood of Nations. https://www.historylink.org/File/10164

Bureau of Land Management records. (1870)

Rochester, J. (2001, June 9). Seattle neighborhoods: Laurelhurst -- thumbnail history. Seattle Neighborhoods: Laurelhurst -- Thumbnail History. https://www.historylink.org/File/3345

Wilma, D. (2001, March 13). Rainier Valley -- thumbnail history. Rainier Valley -- Thumbnail History. https://www.historylink.org/File/3092

Puget Sound Regional Archives. Grantor record. (1876)

Vermont Historical Society. (n.d.). Thomas H. Canfield (1822-1897) papers, 1842-1932 doc 6 doc 7, 8, 163 ... https://vermonthistory.org/documents/findaid/canfield.pdf

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, September 30). Northern Pacific Railway. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Pacific_Railway

Thomas Hawley Canfield Sr. (1822-1897) - find a... Find a Grave. (n.d.). https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/69207929/thomas-hawley-canfield

Tobin, C. (2004, May). North Rainier Valley Historic Context Statement. https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/Neighborhoods/HistoricPreservation/HistoricResourcesSurvey/context-north-rainier.pdf

Residential property records. (1890)

Blanchard, L. (1968). The street railway era in Seattle; a chronicle of six decades. H.E. Cox.

Grantor record. (1899)

The Millionaire’s Row. The moore mansion. (n.d.). https://www.millionairesrow.net/81114thE.html

Givens, L. H. (2017, November 3). James A. Moore is authorized to build a canal in Seattle connecting Puget Sound to Lake Washington. James A. Moore is authorized to build a canal in Seattle connecting Puget Sound to Lake Washington by a bill signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt on June 11, 1906. https://www.historylink.org/File/20465

Flynn, G. (n.d.). Biography of Edward Francis Sweeney (1860 -1923). Brewer. https://www.brewerygems.com/sweeney.htm

Civil War Veterans Buried In Washington State. (n.d.). Civil War veterans buried in Washington state - Jerome Butts. Jerome Butts - Civil War Veterans Buried In Washington State. https://www.civilwarvetswastate.com/veterans/detail.html?veteranid=2106

Puget Sound Regional Archives. Grantor record. (1899)

Puget Sound Regional Archives. Grantee record. (1900)

Puget Sound Regional Archives. Tax roll. (1905)

Puget Sound Regional Archives. Tax rolls. (1910)